INSIDE STORY: Lack of accountability leaves Kairi in limbo

INSIDE STORY: Lack of accountability leaves Kairi in limbo

ARTICLE | MAY 30, 2012 - 8:31PM | BY DR. MICHELLE HARRISON

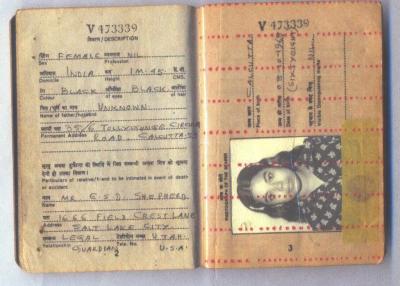

Gibi's passport had the name Shepherd, because Erlene was to have adopted her/ Credit: Dr. Michelle Harrison

Gibi's passport had the name Shepherd, because Erlene was to have adopted her/ Credit: Dr. Michelle HarrisonKolkata - Kairi Abha Shepherd was adopted from India at three months of age and has no country to call home. She was abandoned at birth in a Kolkata nursing home and taken in by a Kolkata orphanage that has since closed. At three months of age she was sent to the United States for adoption by Erlene Shepherd, a widow with six other adopted children. Erlene died of metastatic breast cancer when Kairi was eight years old, but never filed the papers to make Kairi a US citizen.

Now under threat of deportation, Kairi, who suffers from rapidly progressing multiple sclerosis, is an orphan without a country. She is from India, but was not raised as an Indian. She was raised as an American, but is not American. Deportation is a sanitized word. The proper term is exile, the banishment of a person from his home, his country. Given Kairi’s progressive illness, it might be death in exile.

I am an American doctor settled in Kolkata since 2006, where I founded Shishur Sevay, a home for orphan girls, some with disabilities, who were rejected for adoption. I have a younger daughter adopted in 1984 from IMH (International Mission of Hope), the same orphanage as Kairi. I also have an older daughter, to whom I gave birth. Both are American citizens, one by birth, the other by naturalization. When my older daughter was born she was mine and the only papers I filled out were for her birth certificate.

For my Indian daughter the process was longer and more complicated than pregnancy. I carried a different responsibility. I had been entrusted with another mother’s child, to love and raise her as if she were of my body. She had already lost a mother and a family. I felt a special responsibility to be the forever family she had been promised. Everyone in the long chain of people, institutions, and governments had a special responsibility for this child, because at that moment in time, they were the only ones in a position to secure her future safety.

Kairi didn’t hop on a plane at three months of age and say, “Mom, I’m coming home. Meet me at the airport.” Her “line of possession” was from a nursing home in Kolkata, to International Mission of Hope, to an escort, to Erlene Shepherd, her forever mother. An agency from the US side, AIAA (Americans for International Aid and Adoption), had to do a home study and approve Erlene to adopt another child.

Those papers had to be approved by the Indian Embassy in Washington and the US Immigration Service, all before Erlene could be assigned as Kairi’s mother. Back in India, IMH had to show how they received the child, and then petition the Alipore Court to give guardianship to Erlene Shepherd.

The guardianship papers defined the responsibilities of Erlene Shepherd: “Your petitioner submits that she is a fit and proper person to be appointed guardian of the person of the said minor during her minority. Your petitioner further submits that it will be for the welfare of and manifestly advantageous to the said minor as regards her up-bringing, education and establishment in life, if the petitioner is appointed guardian of the said minor and the minor is permitted to be taken to and live with your petitioner in USA.” The guardianship by the government of India did not require adoption or citizenship.

A different government office issued an Indian passport so Kairi could travel, with Erlene’s name as her US contact. The American Consulate had to issue a visa for Kairi to enter the US. Once Kairi was in the US, she would have received permanent resident status (a green card), which she then would have had to relinquish when she received her naturalization papers.

What went wrong – falling through the cracks

International adoption occurs in the context of a government agreement between the sending and receiving countries. At the time of Kairi’s adoption, neither government required that the child become a citizen. In fact they did not even require that the child be legally adopted!

All the people and government officials involved in the process of obtaining the child, caring for her, sending her to the US, and approving the US family were paid for what they did, by salaries or fees. Once Kairi was in the US, no one had a financial interest in helping her to get her papers. There may have been concern, but it was not imperative.

The agency that approved Erlene did so even though she had not obtained citizenship for her other international adoptees. Erlene was also approved to adopt Gibi after Kairi’s adoption. They had a single meeting, with Kairi present, and then the adoption didn’t happen; but Gibi had gone to Denver with Erlene’s name on her passport, just as Kairi had. Today in Kolkata, Gibi is tearful, and says, “Kairi was supposed to be my little sister. Maybe if I had been there to take care of her, her life would have been better.”

Erlene, a single mother with seven children, was struggling financially and then became ill with cancer. The child services agency in Utah which looks after orphaned children did not notice that the children lacked citizenship.

The older siblings attempted to apply for Kairi’s papers when she was 16, but the US authorities did not let them, as they were not her parents.

By the time Kairi was an adult, her life had truly fallen apart. She was on drugs and was convicted of forgery for the purpose of getting drugs, but as a non-citizen, she was suddenly an “illegal alien headed for deportation.” She has been fighting this since 2007. The United States Child Citizenship Act of 2000 created a system of automatic citizenship for adopted children, but it was not retroactive to the time Kairi was born. She missed the deadline by months.

Hillary Clinton said, “It takes a village to raise a child.” First it takes a mother, and Kairi had lost two mothers by the time she was eight. Her mother didn’t obtain the citizenship papers, but the village also failed to notice. The same government that welcomed her at three months wants to send her back at age 30, because she committed a crime. Did any adoptive parent ever think that their children’s remaining in the US was anything other than unconditional, that if they broke the law, back they went? When we adopted, we were the ones on trial as to our worthiness of raising our children. For Kairi, who lost two mothers, the village absconded.

Kairi’s multiple sclerosis – the effects of exile

Kairi’s first symptoms of multiple sclerosis appeared when she was 18, and she was diagnosed at age 22. It has progressed rapidly. She has clear lesions of her brain, which are worse on each subsequent MRI. Without powerful and expensive medications, she will not be able to survive. With each crisis of her MS, she is hospitalized for infusions. Even worse, she cannot tolerate the heat. If Kairi is exiled, she will arrive in India without funds and without a destination. She could literally collapse as soon as she leaves the airport and end up in a hospital with no money and no way of communicating.

The US does not deport in a kindly way. A person is put on a plane with no possessions except travel documents and they are not even allowed to make a phone call. All the rights of Americans that are taken for granted are only for citizens. Kairi has no rights, not even to a phone call to say she is leaving. She was escorted to the US with fanfare, with people sending her off, with people waiting for her arrival. Yet there are no goodbyes, just a disappearance.

When I adopted from this orphanage, I sent ahead an outfit for my daughter to wear for her journey home. We all did that. Kairi went to the US in that special outfit her mother sent her. She will be returning in whatever she happens to be wearing at the time, with no one to meet her, to a country where she looks like she belongs, where people will expect her to respond as an Indian raised in India, but she will be alone, more alone than when her mother left her at the nursing home in Kolkata. Kairi left for America as a healthy infant. She will be returning as a very sick adult with an incurable disease and without any means of survival.

Where is the village now as she faces death in exile?

The US must face its responsibility to the orphaned children it accepted, which at the time was understood to be unconditionally. As an adoptive parent, I didn’t have a return policy. The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 was a good attempt to fix the problem, but it didn’t go back far enough. Kairi isn’t the only adoptee facing deportation.

Another Indian adoptee

, Jennifer Hynes, was sent back to India, leaving two children and a husband in the US. She is begging to be able to return to the US to be with her children.

The law has to be fixed. The process of exiling these sons and daughters of Americans must be stopped. They may be “adoptees,” but they came to the US to be our sons and daughters, as if of our bodies. That is what we owe them.

About the Author

Dr. Michelle Harrison

Doctor, author, educator, and most importantly, mother, Dr. Michelle Harrison is a true visionary. She came to India in 2000, drawn by family connections having adopted from Kolkata in 1984. Over the next five years she returned to Kolkata often, sponsoring children in schools, putting toilets in villages and visiting many orphanages. She established Child life Preserve Shishur Sevay as a model of non-institutional care for orphan girls, some with disabilities, in response to asking herself, “What happens to the children who don’t get adopted?”