In Portugal, mainly children with care needs are offered for intercountry adoption

The Flemish Centre for Adoption gave Portugal a positive assessment for intercountry adoption in 2023. However, there are quite a few questions to be asked about the Portuguese childcare system and the reason why many are offered for adoption abroad. It seems that especially children with care needs are no longer given a place.

'Our country has a long tradition of residential care,' says Guida Mendes Bernardo, director of SOS Children's Villages in Portugal. 'That is still ingrained, especially in the interior. There is a perception that children, especially those growing up in poverty, are better placed in a facility than staying with their parents, because that would give the child more opportunities.'

In 2023, according to the Portuguese government, 6,183 children and young people were placed in care, compared to 263 in foster care. This represents 4% of placements. However, experts agree that a foster family is better for a child than a care facility. "We are concerned about how heavily the Portuguese system relies on residential care," warns Nigel Cantwell, an international expert in child protection. He writes this in an analysis by the International Social Service (ISS), an international network of NGOs focusing on children's rights and safety. This analysis was commissioned by the Flemish Centre for Adoption (VCA) in order to decide whether adoptions from Portugal, and a number of other countries, will remain possible in the future.

In response to the UN Guidelines for Child Protection, the southern European country passed a law in December 2023 that requires all large facilities to transform to a smaller, family-oriented model. The new rules stipulate, among other things, that centres may house a maximum of 15 children per ward, and that each child must have a trajectory supervisor . That transition is now in full swing.

Foster care in its infancy

Portugal also seems to have only just emerged from hibernation when it comes to foster care.

It was only in 2019 that Portugal chose family care over institutional care and decided to expand the foster care system. The above figures show that there is still a lot of work to be done, which is also confirmed by Guida Mendes Bernardo. 'There are really very few foster families and hardly any children who are cared for through this system. Foster care is also unknown. Most Portuguese do not even know the difference with adoption.'

According to Bernardo, the government itself also has the wrong view of foster care. 'They only see foster care as a means to reduce the number of children in institutions, and not as a care measure in itself. That is why it is not sufficiently developed.'

And then there is a third form of care, the so-called kinship care , or care by the child's immediate family. But unlike many other countries, this is conspicuously absent in Portugal. 'There is no official statute for this here,' Bernardo complains. 'That means that the family has no handles on how to deal with the children. Because we do not register and supervise it, it is a blind spot.'

In the meantime, the socialist party PS has reportedly submitted a bill to grant kinship care an official status.

© Nelleke Broeze

Adoption

The ISS analysis, on the other hand, praises the Portuguese efforts to return children to their families after placement, and to avoid placements by supporting families with a multidisciplinary team. It speaks of an 'integrated approach'.

But Bernardo, who manages such a team in her work, immediately qualifies. 'In practice, the employees cannot handle the workload', she says. 'We have to follow up a hundred families per month with three employees. That is crazy.' Bernardo asks for more understanding for the time investment that reunification and prevention require. 'If you really want to see the number of children in facilities go down, then you have to make sure that children do not enter the system in the first place', she grumbles.

Children who do remain in that system and for whom no domestic solution is found, can, according to the subsidiarity principle, as laid down in the Hague Convention, end up on a list for foreign adoption. Since the start of the Flemish-Portuguese cooperation for adoption in 2015, 27 Portuguese children came to Flanders.

Since 2001, a total of 260 Portuguese children have been adopted abroad. 273 children from other countries have found a new home in Portugal. The latter come mainly from countries with a historical-colonial connection: Brazil, Cape Verde, and the archipelago of São Tomé and Príncipe.

It is striking that Portugal both adopts and offers children for adoption. According to the Dutch child welfare organisation International Child Development Initiatives (ICDI), this dual role implies that Portugal could indeed take in its own children. Child expert Nigel Cantwell counters that a solution is always sought for each individual child, and that it is 'theoretically possible' to be both a sending and receiving country. 'But Portugal is the only Western European country that cannot take care of its children. That is unusual', he adds. 'We only agree to foreign adoption if it is impossible to find a domestic solution for a child' , the Portuguese adoption authority responds .

Preferences of prospective parents

Furthermore, it is remarkable that Portuguese children go to foreign adoptive parents. Today, there are many more domestic candidates than there are children on the list. According to a report by the National Adoption Council, there are 208 children for 1,158 prospective parents. In other words, children who are not wanted by domestic parents go abroad.

Later in the report it appears that for two out of three prospective parents the desired age of the child is six or younger. This does not correspond to the children in the Portuguese child protection system, the majority of whom are over ten . 2% of prospective parents want to adopt a child with serious problems, 62% are open to minor problems, and the remaining 36% want 'no problems' in a child.

It is striking that prospective parents can indicate a preference for the ethnicity of a child. In 2023, 43% of candidates indicated that they would prefer to adopt a child of 'Caucasian' ethnicity. According to the Portuguese adoption authority, this is because 'identity and feeling connected to the child are important factors for good parenting.'

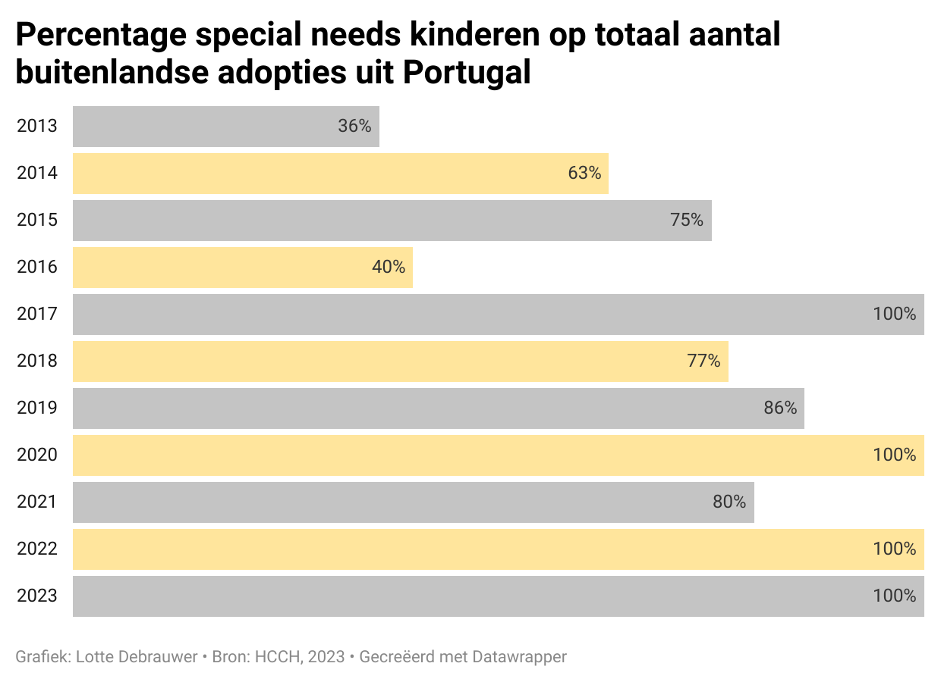

These preferences determine which children go on to intercountry adoption. Figures submitted by Portugal to the Hague Conference on Private International Law show that the percentage of children with 'specific adoption needs' has risen sharply. In recent years, at least 80%, and in some years even 'all' children offered for adoption abroad, are children with specific needs.

Children who need extra care are siblings who are adopted together, children with medical problems, older children, and children with a 'burdensome background', behavioral problems or developmental disorder. According to the adoption authority, it is more difficult for them to find an adoptive family in a 'world where the candidates are mainly focused on healthy children under the age of six'. This is a contradiction that causes difficulties.

© Nelleke Broeze

Failed adoptions

Because sometimes things go wrong. In 2019, three adopted children returned to Portugal because they could not settle in their Flemish adoptive family. This is stated in the screening documents of the ISS and was confirmed by the Flemish Centre for Adoption. According to the Portuguese adoption authority, these children have now been adopted by other families. Pediatric traumatologist Doris D'Hooghe warns of the consequences: 'You uproot the child again after a separation from the biological family. It will not recover from that, that way you really kill the child on a psychological level.'

But there are also more recent examples. According to the report of Portugal's National Adoption Council, there were eight breakdowns or failed adoptions involving Portuguese children in 2023. Five children found a place with a new adoptive family in the meantime. The Portuguese Adoption Authority says that the breakdown rate between 2017 and 2023 was 6%, which is "not high, and comparable to other countries."

'There are many reasons for breakdowns,' says the adoption authority. 'It's about characteristics of both the candidates and the children. And sometimes it's about the matching process.' The authority points to extra care needs, fear of abandonment, and insufficient preparation in children. In the parents, it's about idealizing adoption, a lack of empathy for what the child went through, and impatience in building a parent-child relationship.

Guida Mendes Bernardo of SOS Children's Villages confirms that failed adoptions or breakdowns are a known phenomenon, but names another cause. 'Unfortunately, there is a lack of good aftercare for adoptive families. My brother adopted a child with behavioral problems, but after submitting the papers, no one ever came by again. That can't be right? They are all on their own!'

According to the ISS screening, the breakdowns in 2019 sharpen the contrast between Portugal and Flanders. The Portuguese government believes that the best way to help a child is to place it with a new family. 'It is the best place for a child to develop with affection, stability and recovery from trauma', it says. The Flemish Centre for Adoption, on the other hand, believes that not all children are adoptable because of a traumatic background.

"We refuse children with a complex background or with very clear traumas," says Flemish adoption officer Ariane Van den Berghe. "Within our range of care services, we cannot offer them the necessary support."

Child expert Nigel Cantwell is also cautious. He believes that a failed adoption can be more damaging to a child than growing up in a familiar setting. This attitude is in stark contrast to the Portuguese view. Hélio Bento Ferreira heads a child protection advisory board to the court. 'Adoption comes with risks, just like biological parenthood,' he says. 'Fear of failure of an adoption should not be a reason not to go ahead with it.'

Flanders judges positively

The Flemish Centre for Adoption gave Portugal a positive assessment in 2023. This is important for ongoing cases, and opens the door for future adoptions when the suspension of intercountry adoptions in Flanders ends. In its decision, the VCA did not mention the failing foster care system and the preferences of prospective parents, which allow children with additional needs to be adopted from facilities. And that is precisely why Portugal does not want to let go of foreign adoption.

"Banning intercountry adoption would encourage Portugal to take in hard-to-place children itself," reads a statement on the website of ICDI, which firmly opposes the collaboration .

The Portuguese Child Protection Authority did not respond to our questions after several attempts.