The chaotic and opaque Child Protection Service left Hans 'swimming'

In the years following the introduction of the adoption law, mothers and children were crushed in a chaotic and opaque system. The life story of Hans van Rijssel (64) illustrates the consequences of this lack of oversight. "Child Protection Services made me swim. And I'm still swimming."

After his mother, under pressure from her parents, gave up her son , Hans was initially placed in the "De Kloek" home in Leusden after his birth. After five months, he moved to "Zonnestraal" in Bilthoven, and then lived for more than two years in "Huize Aldegonde." "I was brought in there by the social worker," he recalls. "I stood in that large hall, I turned around, and I was alone. And that's how I've felt ever since."

At Huize Aldegonde , his biological mother and the man she's about to marry try to pick him up. At the home's door, the couple learns that Hans is already living with a family. What they don't know is that he had been taken away just five days earlier. Read more about what happened here.

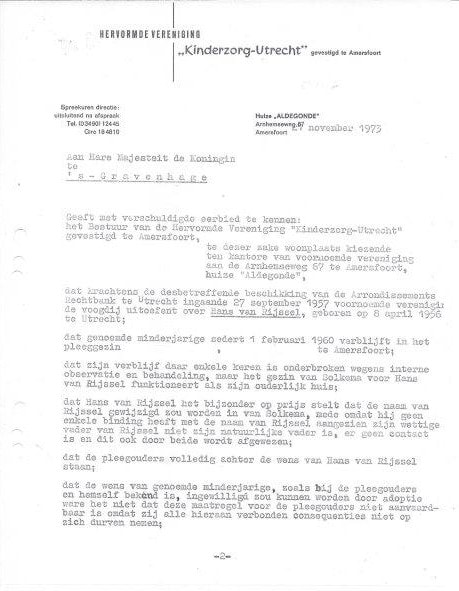

Van Rijssel has nothing good to say about the family he ends up with. Officially, he lived there from age 3 to 18, but in reality, he only spent three and a half years under their roof. The boy was sent to various homes throughout his childhood because he allegedly had behavioral problems. "I was stupid, always did everything wrong," he says. Throughout that time, he was under the guardianship of the Utrecht Reformed Children's Association. His foster parents never adopted him because, according to his file, "they didn't dare accept all the consequences."

What they mean by this isn't clear from the documents, but foster parents received compensation for a foster child. This compensation expired once an adoption was granted.

Hans van Rijssel was under the guardianship of the Reformed Children's Association Utrecht. His foster parents never adopted him because, according to his file, "they didn't dare accept all the consequences."Source Hans van Rijssel file

The Reformed Children's Association Utrecht, where Van Rijssel was a guardian, traditionally cared for children who could not live at home. Over the years, however, Child Protection Services has increasingly also granted them guardianship over children who have been relinquished.

No information for the mother

This contributes to the fog of uncertainty for unmarried mothers. Because they are removed from custody, it becomes more difficult for them to retrieve their child. The guardianship organizations don't always disclose their child's whereabouts, and it takes time to restore custody.

Surrogate mothers and foster children

The adoption law seems to have created its own dynamic in the Netherlands, according to research by Trouw and Omroep Gelderland. One in which unmarried women were pressured to give up their babies or even, decades later, claim to have been forced to give them up. Estimates of the number of women who gave up their children between 1956—when the adoption law came into effect—and 1984—when abortion was legalized—range from 13,000 to 20,000. This is despite the fact that Fiom (Federation of Institutions for Unmarried Mother Care) mediated for 328 children who had been relinquished in the preceding twenty years.

In a series of articles, available at trouw.nl/adoptie , we investigate what went wrong, how it could have gone so wrong, and the impact it has had on people's lives. The stories from Omroep Gelderland can be viewed here.

The Union of Associations for Unmarried Mothers (Uvom) in Amsterdam, for example, which also served as a guardianship organization, takes the position: the less information the mother has, the better. "One never simply discloses the child's whereabouts to prevent the mother from impulsively visiting the child," reads a 1964 letter to Kinderhuis Vliet en Burgh. The guardianship organization responsible for Van Rijssel also failed to inform his mother of the boy's whereabouts, how he was doing, or that he was ultimately never adopted.

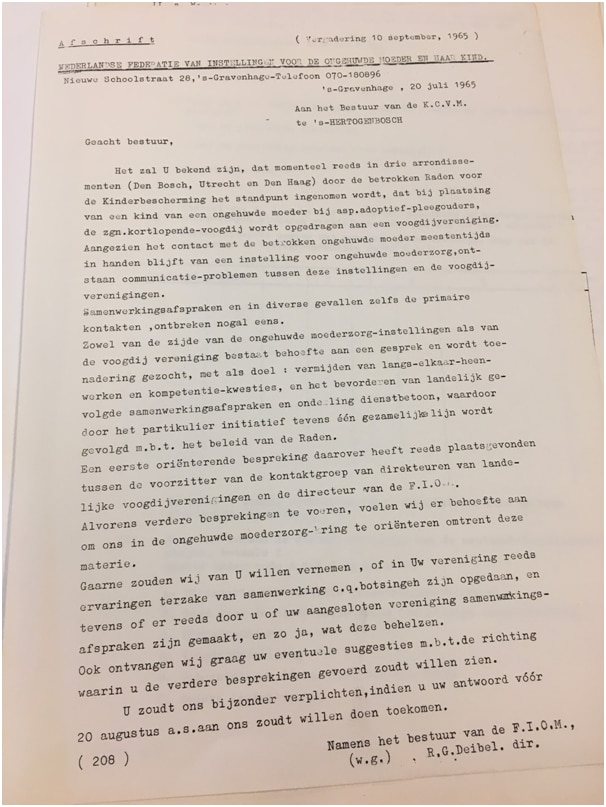

The system made, and still makes, it opaque as to who had or should have had a child in their care at any given time. There is little to no contact between the institutions for unmarried mothers, which have contact with the mother, and the guardianship organizations, which are responsible for the child, wrote Fiom to the Catholic central association for the care of unmarried mothers in 1965.

There is little to no contact between the institutions for unmarried mothers, which have contact with the mother, and the guardianship associations, which are responsible for the child, wrote Fiom in 1965 to the Catholic central association for the assistance of unmarried mothers.Source FIOM archive

Although Van Rijssel was never adopted by his foster family, he discovered while serving his military service that he bore their name. In 1973, the guardianship association submitted a request, saying the boy "would greatly appreciate it." Nonsense, says Van Rijssel. He says he never wanted his foster family's surname and never spoke to anyone from the guardianship association about it. "Those people had two daughters. I think they wanted to pass their surname on to me."

Once he reached adulthood, he changed his surname back to Van Rijssel, the name of the man who recognized him at age three. "That cost me a lot of money; I had to work overtime for it. But that man had guts. He wanted to recognize me without ever having seen me. I respect that."

"Child Protective Services made me swim," concludes Van Rijssel, looking back on his childhood. "And I'm still swimming now." His start in life has an impact not only on him, but also on the next generation. "I did everything wrong that I could do wrong," he says of his interactions with his three children. "Because I didn't know how to do it."

He blames Child Protective Services "for everything," he says. They should have been taking care of him. "I don't blame my mother for anything. The way that period was back then...I don't blame her for that." He's quiet. On the couch next to him sits his wife, his daughter, his daughter's father-in-law. "But yeah, I actually would have liked to have a different life."

The Ministry of Security and Justice, responsible for Child Protection, has declined to comment on the matter. It is awaiting ongoing research into domestic relinquishment and adoption. The Verwey Jonker Institute is currently working on this.

Accountability

For these stories, Trouw and Omroep Gelderland conducted archival research at Fiom, the National Inspectorate of Population Registers, and the Gelderland Archives, and spoke with mothers, children, other stakeholders, experts, and researchers. Previous research and explorations into relinquishment and adoption were also consulted. Sylvana van den Braak searched the Fiom archives. The final approval from the Central Adoption Council was obtained thanks to Eugenie Smits-van Waesberghe.