How Giving Up Your Child Became the Norm

Mother and child belong together was the creed in 1956. But after the introduction of the adoption law, that principle disappeared. How could it be that thousands of women were separated from their children in ten years?

It's August 1967, and in Oosterbeek, nestled in the green space on Nico Bovenweg, the new building of the Paula Foundation is opened. Here, in the coming years, hundreds of unmarried mothers will give birth, and just as many babies will spend their first months, or even years. The modern, new building is opened by psychiatrist Gribling.

His speech breathes a new era. In the past, he says, the guiding principle was: mother and child belong together. But "you will be aware," he continues, "that this principle has been completely abandoned, especially in the last ten years, for reasons so obvious that we can only wonder about its application now."

The adoption law has been in effect for eleven years, since 1956. That law was inspired by the desire of foster parents to also obtain legal parenthood over their foster children. At the time, this involved small numbers. The motto at the time was: mothers, no matter how disabled, must care for their babies. A principle that now holds true again.

The adoption law seems to have unintentionally created its own dynamic

But in the 1960s, that notion was suddenly considered outdated. Even harmful. The adoption law seems to have unintentionally created its own dynamic. One in which unmarried women were pressured to give up their babies, or even, decades later, claim to have been forced to give them up. Estimates of the number of women who gave up their children between 1956—when the adoption law came into effect—and 1984—when abortion was legalized—range from 13,000 to 20,000. This is despite the fact that, in the preceding twenty years, the Fiom (Federation of Institutions for Unmarried Motherhood Care) had mediated for 328 children who had been relinquished.

The actual number of children likely was higher, as Fiom didn't see everything. At the beginning of the last century, children were also advertised through newspaper advertisements or placed with sisters, aunts, or other acquaintances as if they were their own children.

Yet it is clear that a huge shift has taken place. While in 1954 Fiom still knew that four percent of mothers who gave birth in a home gave up their child, ten years later that figure had risen to 39 percent.

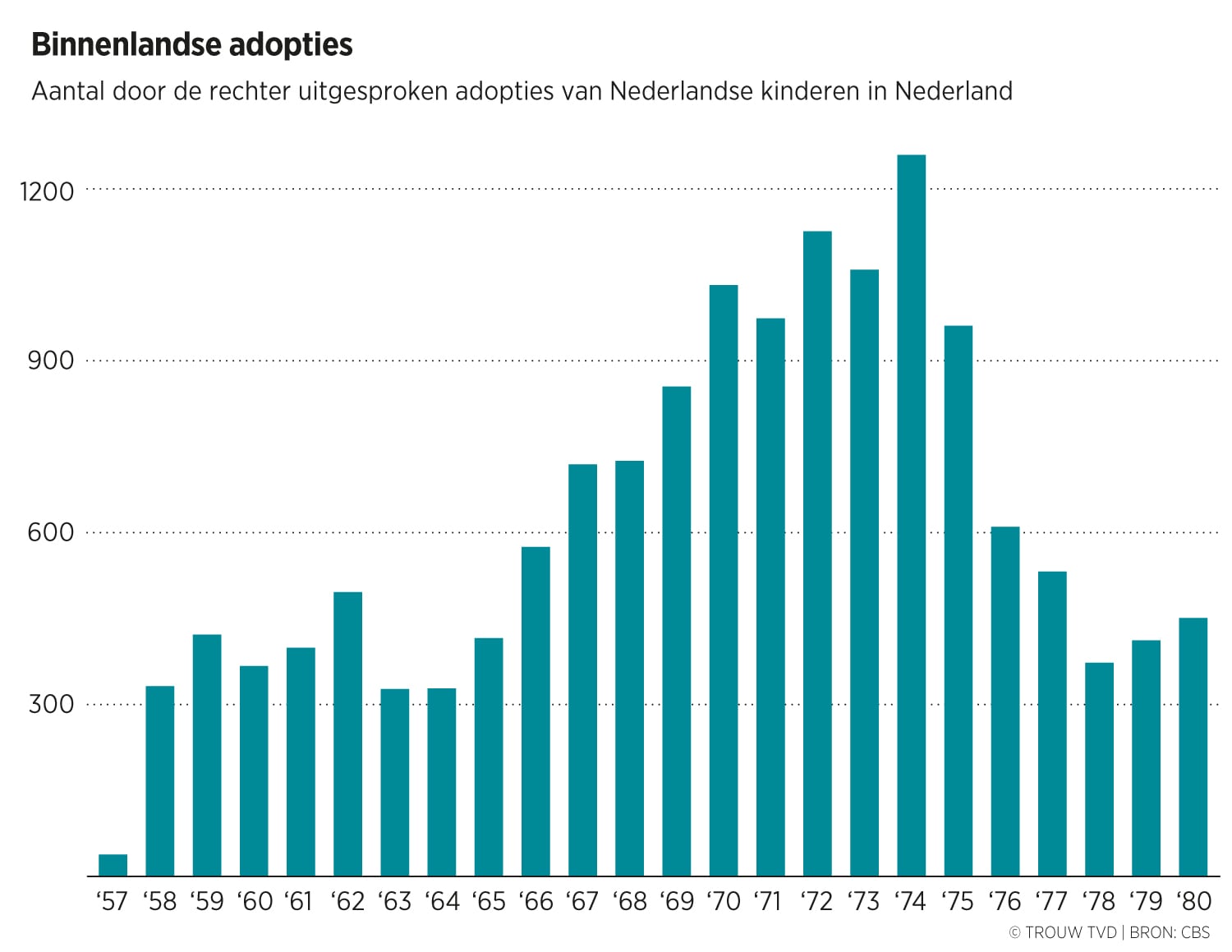

Between 1956 and 1984, over fifteen thousand Dutch children were actually adopted, the majority in the 1970s. At its peak, in 1974, judges granted 1,259 adoptions. That's almost four per day. Because years often passed between a woman's relinquishment and the actual adoption, it's safe to say that the vast majority of adoptees were born in the 1960s. How did it come to this that, in ten years, thousands of women were separated from their children?

Source Thijs Van Dalen

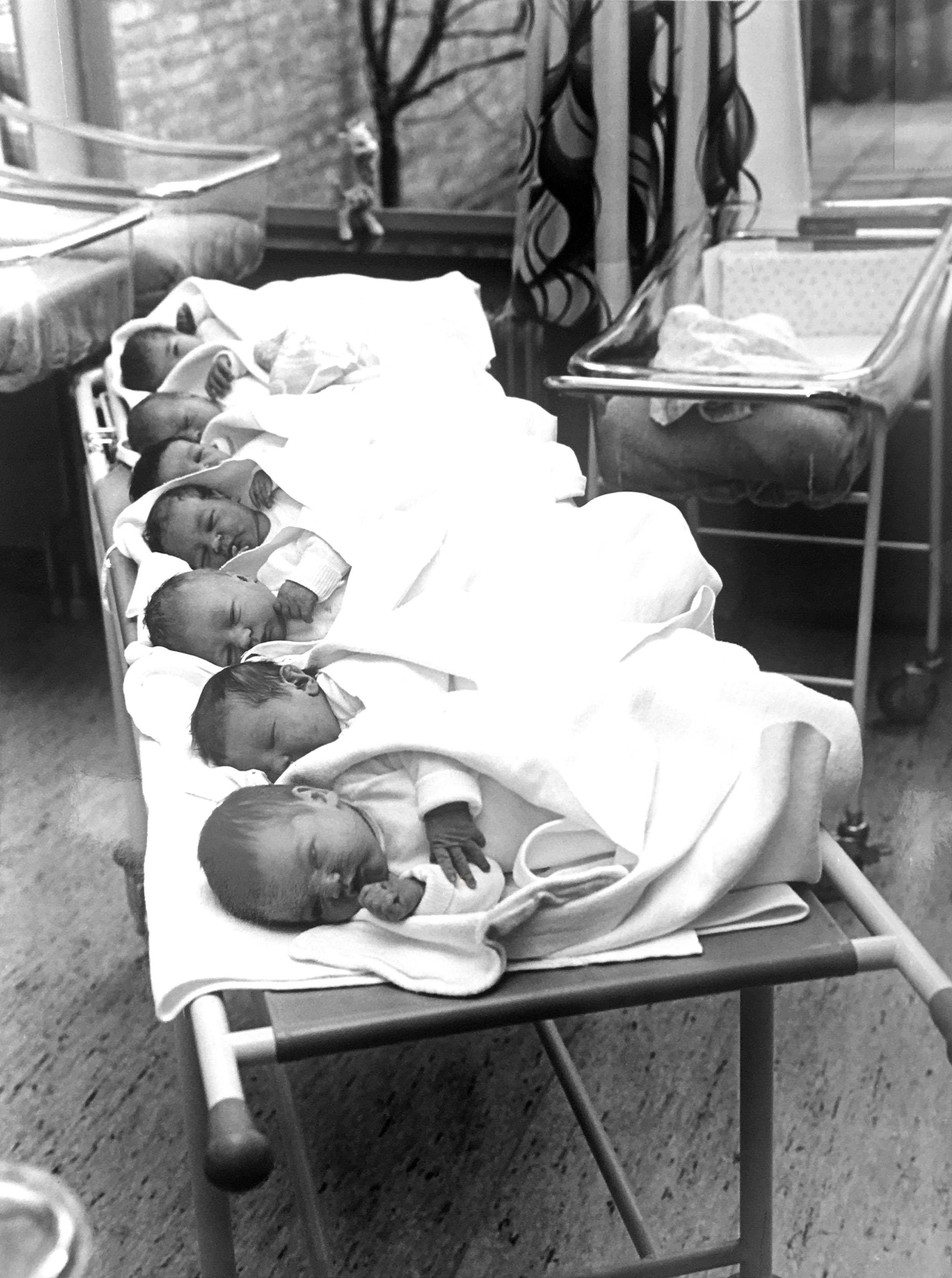

Children in the Paula Foundation shelter.Source *

The sentiment changes

It was the spirit of the times, is a common answer to that question. But that spirit of the times changed in the years after the adoption law was introduced: until the early 1960s, unmarried mothers, regardless of their circumstances, were expected to care for their children themselves. In those first years after 1956, the Fiom organization, which represented 144 institutions for unmarried mothers, still emphasized the principle that mother and child belong together. The federation warns that the adoption law is not intended to encourage the normalization of relinquishment.

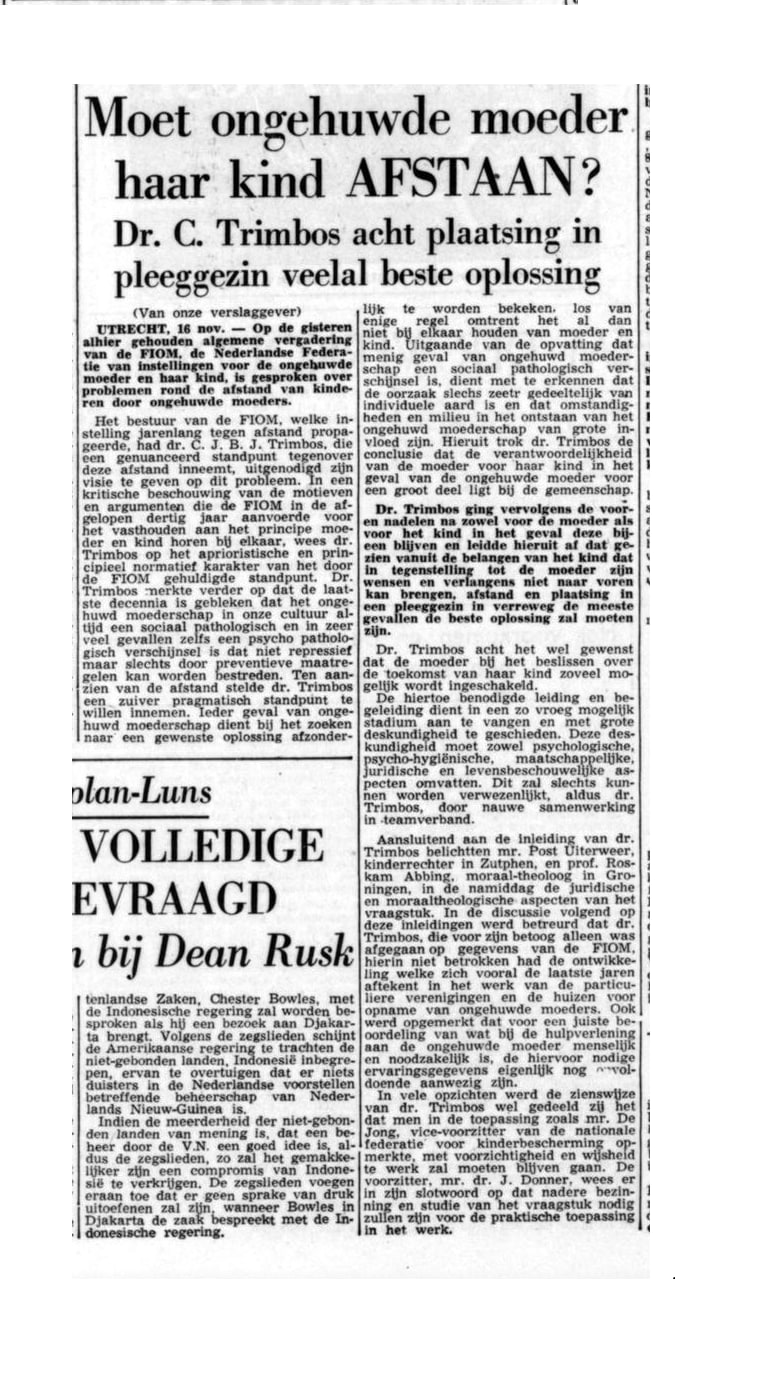

In the early 1960s, sentiment shifted, influenced by the rise of psychiatry and the professionalization of social work. Neurologist Kees Trimbos, a fervent proponent of the idea that separation is best for children of unmarried mothers, was asked to address a meeting of the Fiom association in 1962. He called it "sportsmanlike and loyal," because at that time the association still "advocated" that mother and child belong together.

That idea, he says, is based solely on what's best for the mother, not the child. The latter would benefit from a "real" family, with a father, a family atmosphere, and social status. While he says each "case" must be considered individually, he also reminds his audience that what happens to her child isn't solely up to the mother herself, "because she's not the only one who has to bear the consequences." "As a social-pathological phenomenon, the solution lies at the community level," according to Trimbos. Within that community, "there are also families who don't have children and are perfectly capable of caring for a child."

He therefore argues that the decision to give up a baby should be taken as early as possible, preferably before the birth.

De Maasbode, November 16, 1961. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)Source Delpher / KB

This vision isn't entirely new. Neurologist Trimbos first wrote it down in 1953, together with psychiatrist Han Heijmans. Over the next ten years, they gained increasing influence. Heijmans became an advisory member of Fiom in 1963 and was then director of the Catholic Mothers' Aid office in Amsterdam. Trimbos remained a member of the Central Adoption Council until 1962. This council advises on individual adoptions and the system as a whole.

The position of chair of the Central Adoption Council is also an interesting one. In 1962, it went to Hendrik Cloeck, secretary of the Social Council in Amsterdam. This is the same man who, in 1946, wrote the first dissertation on adoption, including a detailed proposal for a law. A proposal that the final adoption law closely resembles. In 1955, Cloeck also founded the Dutch branch of International Social Services (ISS), which, after World War II, focused on migration and adoption.

Former children's home Aldegonde on the Arnhemseweg in Amersfoort.Source Eemland archive

At the FIOM meeting, which neurologist Trimbos was allowed to open, it became clear how far some people were willing to go, based on the firm belief that an unmarried woman cannot care for a child. A juvenile court judge from Zutphen noted that the law stipulates that adult women may only be removed from guardianship in cases of bad behavior, abuse, neglect, or insanity. This often does not apply to unmarried mothers. So how, he wondered aloud, can we still separate mother and child if the mother resisted, and the law prohibited it? A new legal provision was needed, the judge argued, and in the years that followed, adult unmarried mothers were indeed removed from guardianship because they were "unfit or unable" to "fulfill the duty of care or upbringing."

A professor from Groningen further notes that the mothers in question have committed 'a serious moral crime' and that they therefore no longer have 'any moral right' to their child.

Children in the Paula Foundation shelter.Source MAI van Bommel

You can listen to the podcast that Trouw made about this topic via the player below, or search for it via the usual channels such as iTunes , Spotify or Google Podcasts.

The mood changes

Although these men were also criticized, the mood changed from that moment on. In 1963, FIOM noticed that women in a growing number of transition homes were not welcome for the usual three months after giving birth, but only for about ten days. While ten years earlier, a three-month stay was considered essential for the bond between mother and child. If that proved impossible, for example, because a woman would lose her job, at least six weeks was the goal.

Voor net bevallen vrouwen, die op dat moment nog niet zelfstandig een woning mochten huren, bij familie vaak niet welkom waren en geen aanspraak konden of wilden maken op bijstand of andere financiële hulp, betekende dit veelal dat het wel erg moeilijk was om hun baby mee te nemen als ze zelf het tehuis moesten verlaten.

Daarbij verliest de Fiom, die lang kritisch blijft op het afstand doen, invloed. In 1964 wordt de Fiom-Commissie tot centralisatie inzake afstand van kinderen opgeheven, waarna ongehuwde moeders overgeleverd lijken te worden aan de tijdgeest die zich steeds meer tegen hen keert.

De veranderende norm is ook in de Paula Stichting te zien. In 1961 behoudt ruim 60 procent van de moeders die bij de stichting bevalt hun kind, in 1964 is dat iets meer dan de helft en in 1968, het jaar na de opening van het gebouw in Oosterbeek, doet meer dan de helft van de moeders juist afstand. Waar moeders voor invoering van de adoptiewet nog contact hielden met hun kind in een pleeggezin, worden in Oosterbeek alle banden verbroken.

Lees hier hoe de dan 22-jarige Trudy Scheele-Gertsen in 1968 haar zoon moest afstaan in de Paula Stichting in Oosterbeek. “Wat er met mij en hem gebeurd is, is mensonterend.”

Op de precieze rol van de adoptiewet daarbij, is moeilijk de vinger te leggen.Maar het feit dat adoptie juridisch mogelijk werd, lijkt het fenomeen te hebben aangemoedigd. De Commissie tot centralisatie inzake afstand van kinderen heeft daar wel een gedachte over. Die schrijft bij opheffing in 1964: ‘Ongetwijfeld is door het feit, dat adoptie in ons rechtsstelsel is ingevoerd, de neiging versterkt tot scheiding van moeder en kind’.

‘Adoptiemarkt verstoord’

In 1970 verandert het sentiment en schrijft de Katholieke Hogeschool in Tilburg dat ‘de adoptiemarkt’ is verstoord nu steeds meer moeders hun kind alleen opvoeden. “Het evenwicht tussen vraag en aanbod is verstoord”, aldus een publicatie over ongehuwde moeders die hun kind gehouden hebben.

Inderdaad daalt het aantal kinderen dat wordt afgestaan in de jaren zeventig snel. De bewust ongehuwde moeders komen op, in 1965 is de algemene bijstandswet ingevoerd, anticonceptie komt beschikbaar. De snelle daling van het aantal Nederlandse kinderen van wie afstand wordt gedaan, leidde er overigens wel toe dat het aantal kinderen dat uit het buitenland wordt geadopteerd snel toeneemt.

Zo kan het gebeuren dat vrouwen die eind jaren zestig onder druk of gedwongen afstand doen van hun kind, amper vijf jaar later met verbijstering moeten toezien hoe alleenstaande moeders gevierd worden als het toppunt van vooruitgang en feminisme.

Verantwoording

For these stories, Trouw and Omroep Gelderland conducted archival research at Fiom, the National Inspectorate of Population Registers, and the Gelderland Archives, and spoke with mothers, children, other stakeholders, experts, and researchers. Previous research and explorations into relinquishment and adoption were also consulted. Sylvana van den Braak searched the Fiom archives. The final approval from the Central Adoption Council was obtained thanks to Eugenie Smits-van Waesberghe. For all the stories, a podcast, extensive explanations, and much more, visit trouw.nl/adoptie.